I am not always the most detailed-oriented person, hence my defaulting to extensive list keeping and note taking. However, when presented the chance to cause a mild inconvenience to multinational corporations, I will peruse details like I am clerking for a Supreme Court justice.

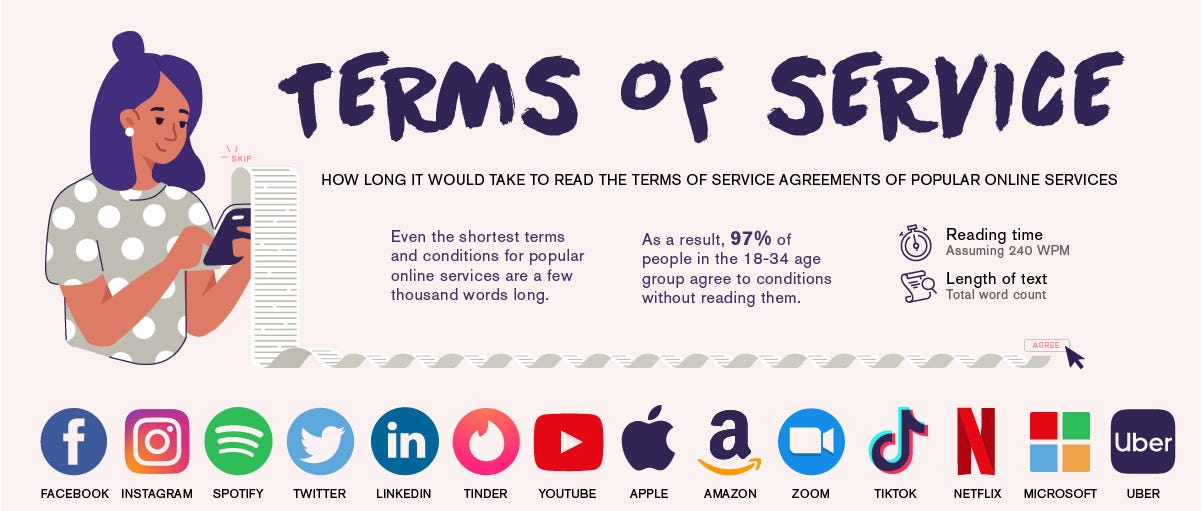

I am referring, of course, to terms of service. Also known as end user license agreements, these are the extensive documents we all lie about having read before opening a new piece of software. These days, everything from your refrigerator to your car comes with a term of service. Dozens and dozens of pages of legal jargon that no one could reasonably be expected to read, let alone understand, without a law degree.

Over the last 25 years, there has been a particularly frustrating trend of legalese buried inside user agreements. Empowered by a post-Regan, post-Bush, corporate-friendly federal judiciary, in the 1990s companies realized they could avoid costly class…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to I've Ben Thinking to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.